The ordnance survey maps of Ireland are a treasure trove of information. The country had been completely mapped by 1846, this was done by a specialised team and included amongst it some people who were very knowledgeable on the Irish language, people like John O’Donovan and Eugene O’Curry. The maps were updated at regular intervals after that and as a result if closely studied can tell us a lot about the changing face of the Irish landscape over the past 200 years. And with a little bit of close analysis, we can also use the early maps to project back even further and help us speculate in an informed way about what the landscape might have looked like for a century or two before that as well.

The first thing to remember is that the population of the country was a lot less at some points in the past than others. In 1600 the population was estimated at 1 million people. Even accounting for the fact that the rate of urban dwellers to rural dwellers was much different to what it became later, this meant that the population in our townland of Lissaclarig was not very extensive at that time.

Three huge events had a significant effect on the population of the country generally over the coming centuries and to a certain extent they can all be mapped onto the life of our townland.

Firstly, there were the Cromwellian wars, when over a short period of about five years the country was devastated. We do not know exactly what the impact on the ground was here, but it is likely that there were significant effects on the local area. This is made all the more likely when we know that Viscount Muskerry the leader of the Confederate and Royalist forces was the owner of local townlands like Skeaghnore. This would have led to confiscation of land with a likely change in some of the tenant population following the defeat. The population of Ireland is estimated to have decreased by 20% in those years due to the war, starvation and plague and as it was arguably the most traumatic shock the country has ever experienced.

The second great demographic shock to the country came in 1740. Due to a very harsh winter the country experienced a very severe famine, it is estimated that around 300,000 people died in that famine, many of them in County Cork which was badly affected.

The third shock is one that we are most familiar with, the Great Famine, An Gorta Mór in 1846-52 which resulted in 1 million deaths and 1 million people emigrating from the country.

After the first two famines the population of the country grew again, in 1600 there were 1 million people in the country, by the middle of the 1700s that figure had well over doubled and in a tremendous expansion of the population from the late 1700s to the 1840s the population grew to some six million people.

Alongside the ordnance survey maps we have the great historical source, the Griffith Valuation of Ireland. The lands of Lissaclarig, Prohoness, Murrahin, and the surrounding townlands in Kilcoe and Aughadown parishes were mapped for valuation purposes around 1848 during the great famine. Valuers travelled from townland to townland valuing the properties so that the government could have a standard baseline on which to tax that value of property. As well as giving us details of the people who lived in the area at the time the Tenant books which are in place for many townlands list the size and quality for all the houses in the townlands.

We do not have Tenant Books for Lissaclarig but through comparing the returns for the neighbouring townlands and closely studying the OS map we can credibly speculate on the houses in Lissaclarig before the Great Famine.

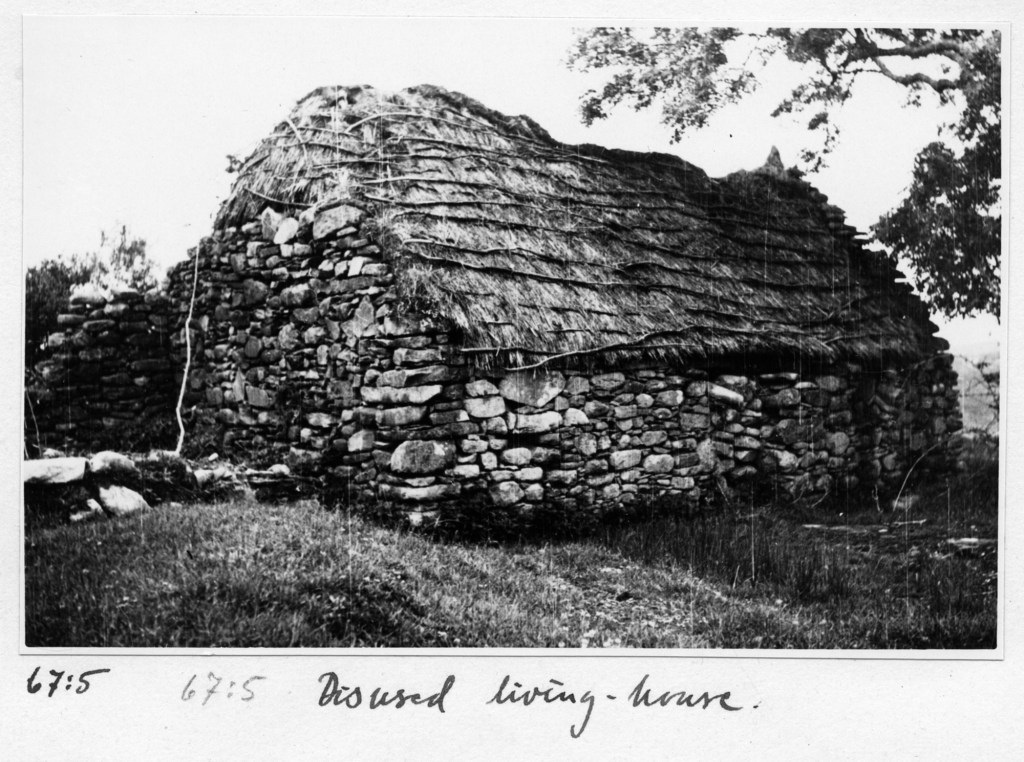

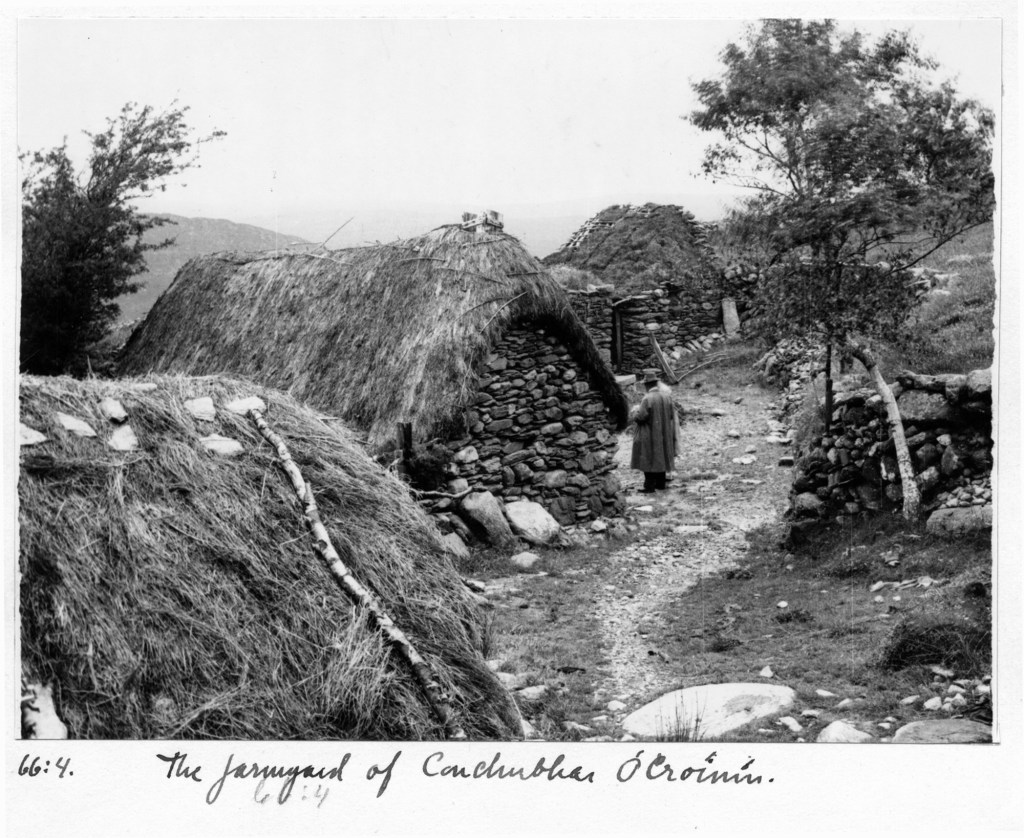

It is unlikely that there were many if any slated houses in the townland in the 20 years before the famine. The farmhouses in the townland and in the neighbouring townlands were significantly smaller than the ones that became the norm after the famine. Most farmers houses were built of stone with a clay mortar. They were largely single storied with thatch roofs. A farmer’s house was typically about 30ft long, 16ft wide and about 6-7ft to the eve of the roof. They would have had two rooms inside with possibly a half loft that was accessed by a ladder or a straight stair. The out houses such as piggery or cow houses, were low small, and thatched.

However, there were also many other houses in the area around 1840. These tended to be small one-roomed cottages built with stone or more often with mud or turf with rough thatched roofs. Some of these buildings had chimneys although many didn’t. The people who lived in these houses lived precarious lives, the land on which they built their huts was the property of the tenant farmer, and sometimes they worked for the farmer and leased a small potato patch from the farmer to feed their own families. These huts were sometimes built along the roadside or on common land. Looking at the original OS map of Lissaclarig there is clear evidence of a small clachan or grouping of small houses in Lissaclarig West to the south of the small ringfort or lios that still stands today. It appears likely that there were at least a dozen if not more houses in an area which after the famine had three family farmhouses.

This image of a settlement in Inchinossig (1935) might be able to give us insight into what the clochán in Lissaclarig looked like.

Looking closely at the OS maps from the 1840’s and 1890’s it becomes clear there are many other houses that existed in the area before the Great Famine that have disappeared in the later versions of the map in the late 19th century.

In the space of 50 years, we can see the number of buildings reduce by more than half.

The fact that they have left such a light impression on the landscape such that they have completely disappeared and there are no traces of them on the ground today is testament to the poor quality of these houses that were produced cheaply by poor people without the funds to create more permanent homes. One would like to hope that these people survived the Great Famine or got safely away to America or Liverpool or London, but one fears that many of them ended up in the Abbey Cemetry in the mass grave opened up during the Great Famine.

Footnotes

- The maps were sourced from the ordnance survey of Ireland, using their ‘GeoHive’.

- All photographs were found on duchas.ie, from their photograph collection.

- The photo of ‘Harringtons Hut’ came from The Illustrated London News.